On a lighter note…

THE KILLER BEES ARE COMING!!!!!!

It is the spring of 1990 in Huerta Grande (which, in Argentina, means it’s somewhere between August and December). I’m sitting in my 7th-grade classroom, wearing my guardapolvo, one be-smocked hooligan among many, awaiting the teacher’s return from the main office and, if that day was like any other, paying more attention to my friends across the room than to the book in front of me. Just another school day at Escuela Bernardino Rivadavia.

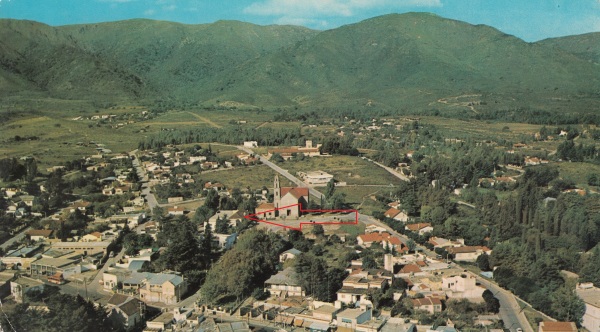

The sleepy little town of Huerta Grande, in Valle de Punilla. The school is indicated by the red arrow; my classroom was at the far end of the building, across from the Catholic church. (Sidenote: I got into my first fistfight ever in the little plaza across from the church,,,)

By way of introduction, it’s important that I let you in on a little secret about Argentine public school classrooms. For the most part, they’re human zoos waiting to happen. I know that classrooms here in the United States are also prone to outbreaks of jinks comprising various altitudes–high, low, and in between–but chaos tended to be the rule rather than the exception in our school, at least when I was there in the late ’80s. (If that tendency dropped after I left, I can only say it must have been a complete coincidence.)

An illustration: My aunt and uncle visited us in Argentina during my 6th-grade year, and in the course of their stay they decided to come and see what a day in the life of a public schooler was like. Our teacher had a way of disappearing to the principal’s office or elsewhere and leaving the room unattended for ten, maybe twenty minutes at a stretch, and–being the mature young adults that we were–her exit from the room generally signalled our exits from our seats. On the day my relatives stopped by, she had left, and in the interim we had spotted a spider on the ceiling of the room, some fifteen feet up. My poor aunt and uncle chose that exact moment to enter and encountered a scene more akin to a monkey habitat than a schoolroom: fifteen or so boys in white smocks jumping from chair to chair, leering like idiots, hurling their little pink erasers into the air in an attempt to dislodge the unfortunate arachnid, who was beginning to have a very bad day indeed. Meanwhile, the rest of the class clapped their hands and cheered us on. (Did I say “us”? Of course I meant “them.”) The look of sheer bewilderment on my aunt’s face was beyond comical–she, a special-ed teacher herself, had clearly never seen anything like it in her life.

Anyway, the parameters having been established, back to our story: a spring day in 1990, twenty-odd not-so-studious sardines stuffed into a less-than-scholastic, whitewashed can. Everything normal, everything as it should be. No reason to suspect that, just two or three miles away, the hammer was about to fall.

Two blocks from my house, the main highway between Huerta Grande and the neighboring town of La Falda forked, one branch remaining a highway (a very steep, wind-ey highway–great for bike-riding) while the other branch took off through the center of town. As we students went calmly about our business, a truck hauling a load of very vigorous honey bees missed the split, overturned, and dumped its cargo all over the pavement. Elated at their unexpected freedom, the bees (some of which ended–literally–by taking up residence in our storage shed) promptly converged upon an innocent passerby and stung him mercilessly. The poor man, who happened to be allergic, of course became deathly ill and collapsed. Ambulances were called, the cops stopped by, crowds thronged–all in all, it was a fairly decent commotion, perhaps even a hullabaloo.

News of the unfolding drama spread quickly, making its way toward the schoolhouse, inexorably, like a twisted game of Gossip. As it went, curiosity became concern, concern morphed into fear, and fear turned into outright hysteria. By the time the tidings reached us, the convergence of trepidation, speculation, and imagination had conjured up a story to chill the heart: A swarm of killer bees was on the loose, and they were headed straight for us.

As you may recall, it was the spring of the year, and the outside world quite pleasant. Cool breezes abounded, and the nascent aroma of flowers was in the air. And our classroom was lined with three pairs of six-foot double windows, every one of which stood opened wide, welcoming the mild weather.

Señorita Sarita, one of our two teachers and vice-principal of the school, who had stepped out momentarily, reappeared dramatically in the doorway of the classroom, her expression and bearing a cross between Jessica Rabbit and Cruella DeVille. In Shakespearian tones, she exclaimed: “Killer bees are coming! Shut the windows!” Or something to that effect. All we heard was “You are all going to DIE!!!”

As she rushed to swing to and seal the first pair, a lone bumblebee floated lazily through the opening and into our midst. And all hell broke loose.

Suddenly that 7th-grade classroom presented an unfavorable comparison to a crowd of metalheads at a Megadeth concert or a department store parking lot on Black Friday. Girls screamed, boys screamed at a slightly lower octave, and everyone headed for the opposite wall. Quickly. We must have looked like a stampede of newly-sentient windmills rampaging through the countryside. The din was deafening; the bumblebee must have been scared half to death; the teacher tried desperately to retake the reins and arrest our terror before we did ourselves an injury. And in the midst of weeping and wailing and smashing of classmates, the poor beast, black hairs now decidedly gray, fled quietly back out the way it had come. I suppose. No one really knows. Perhaps it cowers still in a dark corner of the classroom, now a distinctly antisocial insect, telling other wayward creatures in hushed tones of that dark day it took a wrong turn and wandered into pandemonium.

I’ve often been told in the years since that I’m an unfeeling wretch, because in the face of impending disaster I just don’t seem to care. But it’s not that I don’t care. It’s that, every time someone screams about the sky falling, there’s this mental image that I cannot shake. Y2K, the bird flu, SARS, Valentine’s Day 2003 when the terrorism threat level went up and newscasters told me to Saran-Wrap my home and hold my breath–each time this happens, I find myself back in that 7th-grade classroom, and Señorita Sarita stands once again in the doorway, eyes wide, proclaiming our coming demise…

…and then I think of that poor bumblebee, shaking violently and mumbling to itself, oh so quietly, “What the hell was that?!?”