On July 19th, 2010, the good people of Butler, Missouri gathered around the town square and formed into ranks, aiming flashlights at the sky to spell out the following message: Butler Shine On. While many found this to be a Mayberry-esque gesture, the sound and fury typical of small town life (a throwback to Main Street, USA), it underlines a developing irony which ought to give pause to the most jaded of observers. It asks the increasingly important questions of how long places like this small Missouri town will be able to shine, and how long it will be before no one but ghosts remember it was ever there. How long before Butler (and other places like it) disappear beneath the onslaught of interstate upgrades and interchange-oriented marketing that tend inevitably to drain the life from Mom and Pop culture like a giant, postmodern economic vampire? More importantly, who will miss it when it’s gone?

There’s a name for those of us who give in to this sort of historical and cultural melodrama. Primitivists, we’re called–people who can’t deal with development and so hide behind the myth of the Golden Years. Miniver Cheevy, born too late, too caught up in chivalric illusions to recognize them for what they are: an idealized fiction, and nothing more. Fine, then. I am the first to concede some level of idealization of the past on my part, and there are cases in which such pretensions go too far, obscuring ugly truth behind a beautiful lie. The myth of the Founders and the bold American experiment tends to block from view the very real and quite contradictory endurance of various forms of racial, sexual, and social discrimination within the framework of American democracy. The British Empire basks in a glory undeserved when one begins to look at the everyday details of imperialist affairs. Oversights such as these harm the study of history, and must be addressed honestly and openly in order to weed fact from fable, in the interests of preserving an accurate picture of that which came before. But to assume that all praise of the past amounts to naive primitivist idealism is also to risk a skewed picture of history. Not all progress is truly progressive (culturally speaking), and not all backwards-looking is a sign of backward thinking. Most, if not all, existing societies are nearly enough removed from an agrarian origin that memories of that state are easily accessed by the general public, but make no mistake–we are being pushed, steadily and inexorably, beyond that moment of recall. And when that ability disappears, so much dies with it. There are in Main Street diners characters and voices you cannot find, telling stories you may never hear, in an interstate McDonalds, moments historical and vital (whether the macro-historian appreciates them or not) that say more about Americans as a people–as they were and as they are–than any comprehensive survey ever could. These are the days of our lives, and the sand is running out.

In Butler’s case, the future may be closer than anyone likes to think. I-71, the highway connecting it with Kansas City to the north, is in the process of being upgraded right now, to form a transport corridor running to Shreveport to the south. Regulations governing this sort of development spell disaster for small, traditional communities constructed on the town square model. Controlled access is required, which means the loss of all intersections not involving over- or underpasses, and possibly some that do. Speed limits are legally higher, allowing for quicker passage and less time to observe passing scenery (creating the famed “blink-and-you-miss-it” phenomenon). Legal minimums call for shallower grades and wider lanes, leading to blasting and the exercise of eminent domain. The interplay of these factors can create a domino effect which will lead ultimately to a decline in the quality of life of surrounding communities. Follow along:

In the first stroke, some towns may be cut off from major trafficways due to the closing of intersections or exits. If a toll is added, with the concomitant give and take of complicated amounts of money upon entering or exiting a toll road at irregular intervals, the situation becomes even more drastic. Many motorists will avoid exiting in untimely places to avoid having to deal with refunds, repayments, and receipts, so some towns will, while within sight of the highway, still not be able to net any custom from the people using it. Added to this is a possible increase of speed limit, heightening the tendency of multilane travel to focus on destination rather than journey. This means that all the potential stops along the way also cease to matter, except insofar as fuel stops are required. In this situation, a town’s economy is reduced to two things: its gas stations and its fast food restaurants.

If these gas stations and fast food restaurants know what’s good for them, they will go where the people are, which in this case is highway-adjacent. The fast-moving traveler will likely visit the first place he sees, so the vicinity of interchanges will become a thicket of marquees and signposts, each gaudier than the last, competing for the diminished attention span of the 21st-century pilgrim. Furthermore, these crowding businesses must come from somewhere, and in the case of many small towns, they come from within. Suddenly the town square, with its generations of tradition, begins to shrink, shops close, smallholder groceries throw in the towel, and the world becomes populated by Wal-Mart and 7-Eleven. Before long, even locals are forced to head for the highway to do their shopping, and what was once a rich cultural center–the square–devolves into a quaint reminder of days gone by. The logical conclusion of this process is a town folded in upon itself, imploded by “progress,” and a wealth of lore lost to the need for ever more speed and convenience.

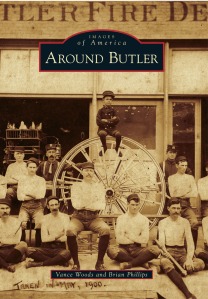

Because, behind the impenetrable barrier of highway business lurks a surprisingly delightful story of a folk, the truest expression of that “public history” thing that’s all the buzz lately. Towns like Butler have it all, from the decidedly ridiculous to the disastrously tragic. The infamous photograph of the self-appointed SWAT team, posing a la Rambo, ammo belts and all, with a stash of illegal automatic weapons–the source of the moniker “Mayberry, USA.” Order No. 11, issued by Brigadier Gen. Thomas Ewing on August 25, 1863, which called for the Sherman-esque incineration of four counties–including Bates, of which Butler is the seat–in order to take down Quantrill’s Bushwhackers. The honor of being the “Electric City,” first town west of the Mississippi to generate its own electricity, and of boasting, at Oak Hill Cemetery, the world’s smallest tombstone (certified by Ripley, believe it or not). And, like every other border town up and down the Missouri-Kansas line, touted by its residents, somewhat a-historically, as “the city where the Civil War began.”

While to the historian concerned with major, earth-shattering, paradigm-shifting events these details may seem to be mere footnotes on a much larger page, to the people who lived them, they are everything. True or false, amazing or asinine, they give shape and meaning to the ways of the human psyche in a manner unmatched by the broad and sweeping narratives so familiar to the high school history student. In these stories I can look at individuals, really look at them and talk to them and give them a voice. They may not be Napoleons or Washingtons, and they may never (really) have started a war, but they are captivating in their own right, and well worth the study. However, as the transportation arteries of our nation become more and more clogged, the opportunities for such study fade into the blur of passing countryside, obstacles to be overcome rather than objects to be weighed and reveled in.

Wendell Berry said it best: “The difference between a path and a road is not only the obvious one. A path is little more than a habit that comes with knowledge of a place. It is a sort of ritual of familiarity. As a form, it is a form of contact with a known landscape. It is not destructive. It is the perfect adaptation, through experience and familiarity, of movement to place; it obeys the natural contours; such obstacles as it meets it goes around. A road, on the other hand, even the most primitive road, embodies a resistance against the landscape; it seeks so far as possible to go over the country, rather than through it; its aspiration, as we see clearly in the example of our modern freeways, is to be a bridge; its tendency is to translate place into space in order to traverse it with the least effort. It is destructive, seeking to remove or destroy all obstacles in its way. The primitive road advanced by the destruction of the forest; modern roads advance by the destruction of topography” (The Art of the Commonplace, 2002).

In the face of clear and present danger, how do we respond? It is not exactly feasible to suggest returning to the old pioneers’ practice of trail-blazing; multi-lanes are here to stay; there is no sense in tilting at that particular windmill. But it is absurd to suggest that they are the solution to everything we seek from travel. Even those who want nothing more than to arrive quickly at their destination will not necessarily find their needs met by them. Just try navigating what seems to be ubiquitous construction work, and you will see that what we erect as a solution to our problems actually becomes little else but an obstacle in itself. Even our attempts at speed are foiled by our desperate pursuit of “progress.” So, what is the answer? Is there an answer? What do we do? How do we keep our little histories from drowning in a sea of asphalt and gasoline fumes?

First, let us not forget that the only real destination is death, a comforting reminder which should prompt us to SLOW DOWN, look around, and take a breather now and then. A lesson I have been trying to teach myself slowly over the last several years is that I don’t always have to be in such a hurry. If I’m bleeding from the head and headed for the emergency room, then sure, fast I’ll go, but otherwise, where’s the fire? The back roads beckon. Perhaps I’ll get stuck behind a semi on a winding stretch of uphill climb; maybe I’ll get bogged down in a never-ending series of four-way stops and small town speed zones. But, also, maybe I’ll see some things that interstates just can’t show me, or eat some food that, while perhaps not Food Network-worthy, still demonstrates the skills wielded for centuries by moms and grandmoms the world over. And the best part is, we’ll still get where we’re going. We’ll just enjoy it more along the way.

More importantly, though (and here I call on my fellow historians, professional and otherwise): forget the French Revolution and the Gettysburg Address. They’ve been done (and then some). Instead, shift your gaze to the people around you, to the (perhaps tiny) world you yourself inhabit, because these things are why macro-history matters, without which earth-shattering events could not happen in the first place. If we lose these stories, it won’t matter who said what, or what battle happened where, and on what day. Wars are fought by and for people–how many people died on a given day is nothing but a number if we don’t ask who those people were when they lived. And no, I’m not suggesting that the bigger picture isn’t worth research and writing. What I am saying is that, too often, the stuff we think of as the bigger picture is really only the picture frame. The lives and deaths of the men and women of Butler (and other towns like it), their cares and conquests, hopes, dreams, and failures–those are what really constitute the “bigger picture” we claim to be building by setting them aside.

If Butler is to “shine on,” then it’s up to the historians among us to flip the switch. And, no, not by searching for proof that the Civil War really DID start there. It’s not about the people of Butler finding a way to change history, it’s about the ways in which they build history on a daily basis. Somewhere, underneath the rubble of a concretized world, lurks a living core of memories and moments in time that, if resurrected, if unearthed with care, may provide a key to who we are, where we’ve been, and where we’re headed–in short, the key to all the history books we THINK we already understand.